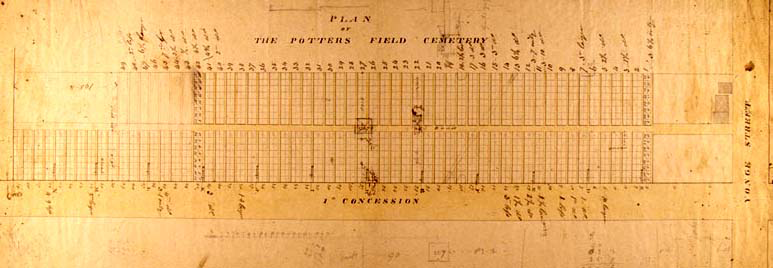

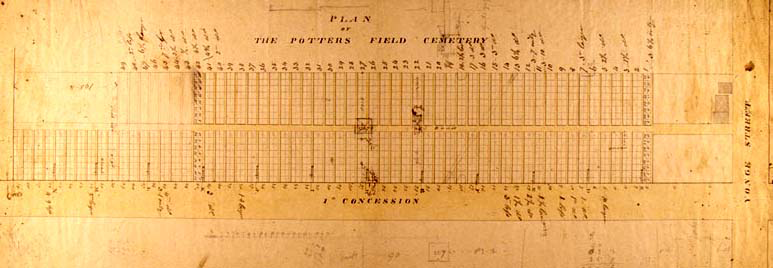

Potters Field and the Roots of Mount Pleasant Group

Most Toronto residents are familiar with the Mount Pleasant Cemetery in mid-town. A sprawling oasis ...

Discover our history, properties, and perspectives along with the latest MPG news.

Most Toronto residents are familiar with the Mount Pleasant Cemetery in mid-town. A sprawling oasis ...

For decades, cremation was separate from the funeral experience. The funeral would end and then the ...

As our society becomes ever more complex, many people are seeking to inject some simplicity and auth ...

The people who choose careers as funeral directors or cemetery staff usually do so because they want ...

As a funeral and cemetery provider, we understand how devastating the pandemic has been on GTA commu ...

As long as people have mourned, others have stepped in to support them. But the way we mourn is alwa ...

The Elgin Mills east side expansion didn’t just add 34 acres of land and decades of use: it offere ...

For 105 years, members of the Salvation Army have gathered at Plot R, Lot 21 of Mount Pleasant Cemet ...

To experience the loss of a loved one during a pandemic is to have grief compounded by challenges th ...

When the first crematorium opened in Ontario at the Toronto Necropolis in 1933, cremation was used i ...

Cemeteries have the potential to be urban oases, where we turn off from the hectic streets to find o ...

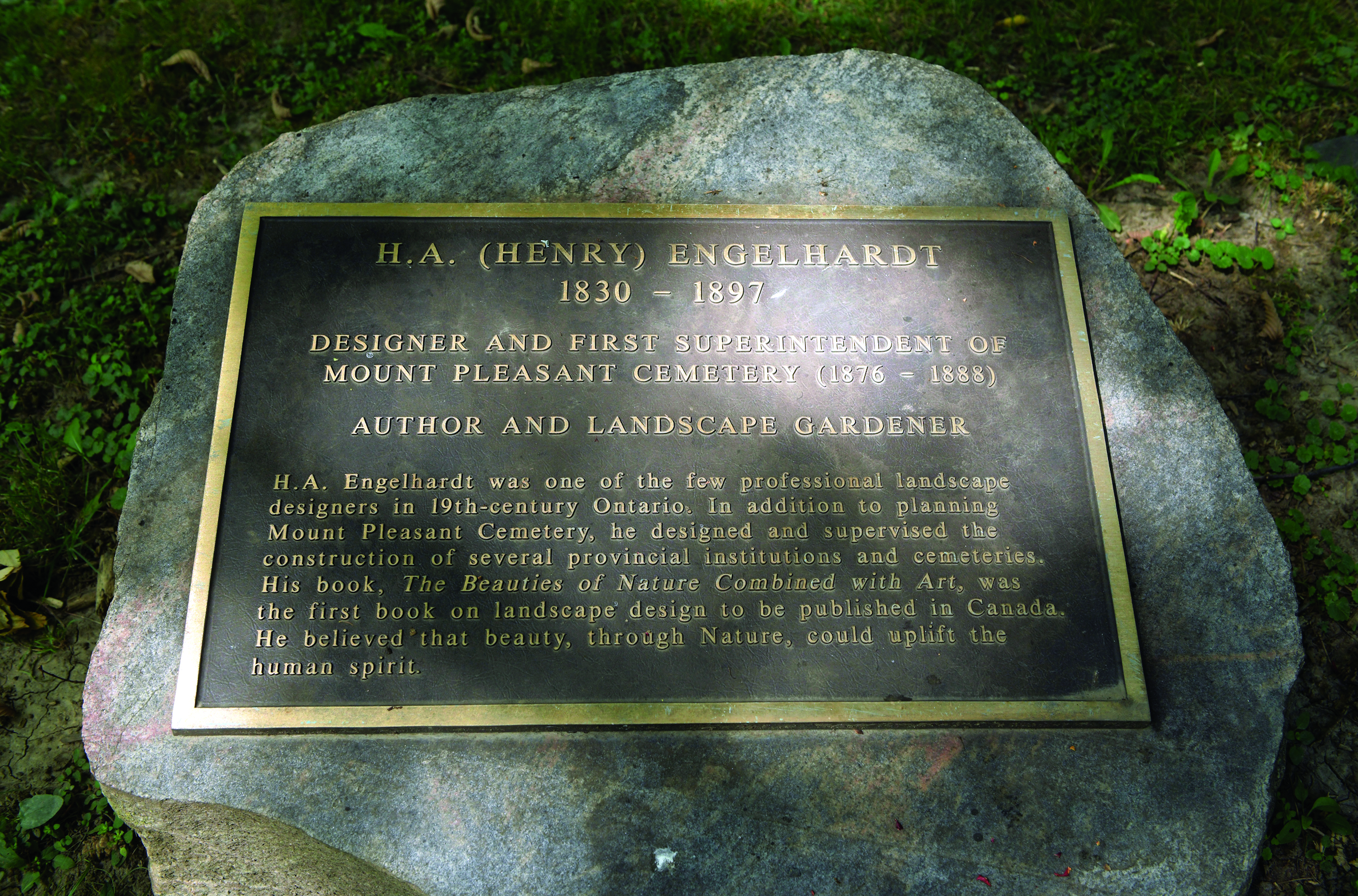

In 1851, a 21-year-old Prussian immigrant stepped off the docks at Baltimore Harbor and began a care ...

“We think that to perpetuate sectarianism even beyond the grave is very preposterous…” With th ...

In May of 2019, the Mausoleum of the Madonna at Beechwood Cemetery opened its doors on a new chapter ...

Elgin Mills Cemetery turned 40 in 2019. But that doesn’t mean it’s stopped growing. The 143 roll ...

To many people, cemeteries are simply part of the background of our lives. It can seem as though the ...

Our front-line teams connect with GTA families every day, often at some of the most difficult points ...